|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

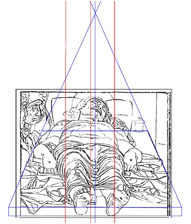

Within Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, the image of Christ has been similarly anamorphically manipulated in order to reconcile the idealized compositional and aesthetic harmony of the scene with the anatomical correctness of Christ’s body. Owing of the unusual viewpoint from which the viewer observed the recumbent Christ, adopting an intimate location at Christ’s feet, Mantegna’s composition yields a distortion in the body of Christ that is not proportionately or perspectively correct. Mantegna did not apply a purely mathematical and formulaic approach to composing the painting. Mantegna was applying Alberti’s concept of Historia * in order to offer a more dramatic and empathetic representation of the Dead Christ. Alberti’s Historia is imbued with “expressions, gestures and emotions of the figures … leaving more for the onlooker to ignore about his grief than he could see with the eye.” (Greenstein, 1992)  Fig. 1. Diagram showing the acute foreshortening of the painting - The overlaid circles expose the acute foreshortening In Mantegna’s Dead Christ, the spectator’s emotions are clear: intimacy and shock (fig. 1). Mantegna’s manipulation of the canon of perspective has been executed in order to bring Christ’s head forward, so that it appeared closer in the foreground and therefore with a greater immediacy and intimacy than would conventionally be achieved had the painting simply been rendered through the systematized application of perspective alone. Mantegna’s Dead Christ is an example of the kind of pictorialism that began to develop late in the Renaissance that deployed Alberti’s system of perspective but denied its systematic control over the pictorial composition as a whole through the painter’s commitment to the composition’s Historia. The horizontal plane is organized, traced out through a grid, with bodies arranged in a tableau of balanced gesture, posture, and mannerism.

Fig. 2. Perspectic Grid

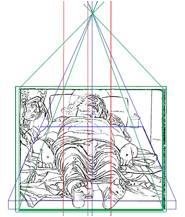

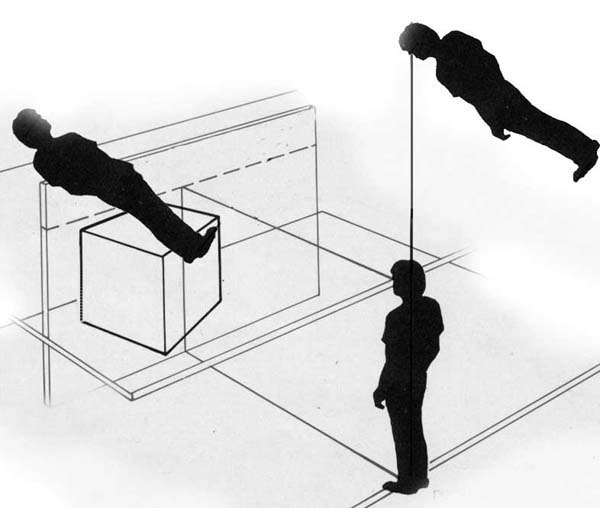

It is probable that Mantegna was using a double point of view (fig. 9-9a-9b). The first (blue lines) is relative to the marble bed, coinciding with the frame (green lines), the second (red lines) is just relative to the body of Christ. (Gherardi, 2009) Under a proper perspective Mantegna’s Christ would have been very awkward: tiny head and legs taking over most of the painting. But people are usually more interested in faces than feet, hence Mantegna struck a balance between dramatic foreshortening and showing the face of Christ.

Fig. 3. Double point of view used by Mantegna Robert Smith has demonstrated through photographs (Brisbin, 2010) that the figure of Christ corresponds to the proportions of a figure seen at a distance of 25 meters. The slab on which the figure is lying contradicts this calculation because it has the perspective scheme of a distance of approximately 2 meters. When a real figure is viewed at a distance of 2 meters the body’s proportion appears distorted; the size of the feet become very large when compared with the size of the head. One interpretation of this contradiction is that Mantegna did not apply the perspective distortion to the figure because it does not have the same linear qualities of the slab. * Alberti defined the concept of Historia in his second book On Painting as a compositional ideal, observing that “painting possesses a truly divine power in that not only does it make the absent present (as they say of friendship), but it also represents the dead to the living”. (Greenstein, 1992) ** The point of origin or termination of bundles of rays or projecting lines directed to a point object, for a photographic image or drawing, respectively.

|